In the god-list An:Anum (53), the title of balang servant-gods was written with the logogram GUD.BALAĜ, where GUD is the logogram for the bull.

The Germanic Gott and the English God come from another Indo-European root, Go, which surprisingly means "the bull".

p. 49, Gods of Love and Ecstasy: The Traditions of Shiva and Dionysus by Alain DanielouThis is exactly what I had figured as the bull was the last animal to be domesticated:

According to the Late ritual for covering a kettledrum—the instrument that eventually took over the role of the Balang-harp—the spotless black hide of a bull never touched by goad or stick became the drum head and its vibrations on the drum the transformed heartbeat of the killed bull turned kettledrum-god. [51] I assume that this Late ritual already existed earlier in some form and was applied to the leather covering of musical instruments with bull hide resonators used in cult. The use of bull hides for Balang-harps is attested in administrative records (36, 41, 42b) and the Balang-harp is called a bull (comment to 4g, 21, 49b). Its sound was the transformed bull’s vocalizations.

From bull to god was a small gap to jump in Mesopotamian culture: anthropomorphic gods carried horns on their headgear, betraying an original bovine nature. According to the ritual, it happened by way of the death of the bull. It was important that it was not a working animal, not touched by goad or stick in the ritual, even less touched by civilization in the OB version of the oratorio Uru’amma’irabi an undomesticated aurochs bull.

Sumerian - just as the Tamil Bull Nandi is a sacred God - the ancient Dravidian-Sumerian connection:

So then God was the Lyre to control weather:Balang-gods were given the title GUD.BALAĜ in An:Anum, a term translated as mumtalku ‘the one with whom one takes counsel, confidant’ in KAV 64 II 17. The same function was expressed in Sumerian with the title ad-gi4-gi4, literally ‘sound repeating’, in conventional translation ‘adviser’, or as we might say ‘sounding board’.Gabbay (PHG:103–109) pointed out that the designation GUD.BALAĜ is restricted to An:Anum, not attested as Sumerian word, and probably a logogram of ad-gi4-gi4 ‘adviser’. He quotes in favor of his understanding An:Anum II 94–95: dad-gi4-gi4 = ŠU (‘same pronunciation’, that is, adgigi), dMIN (that is, dad-gi4-gi4) GUD.BALAĜ (written GUD.BALAĜ) ŠU (‘same pronunciation’).

“(Sumerian) Harpist (= Akkadian) seer, BALAĜ = lyre.” [62]

The conventional transliteration of the word for lyre is gi-na-ru12-um. The sign GI was used to write /ki/ elsewhere in Ebla texts, and the Hebrew word, kinnōr begins with /k/. The word na-ṭi3-lu-um has been understood to mean ‘to raise one’s voice’. [63] In Akkadian, it means ‘to raise one’s eyes, observe’, and at Mari is also as substantive, ‘observer’. An observer (igi-du8) working with the balang instrument, used to control weather-storms, is attested in Ur III texts (29, cf. Section 3c2).

The Sumerian expression “its porch of the balang was a princely sounding bull (21)” may refer to the fact that the cover of the soundbox was a bull hide rather than to the actual cattle-like sound.

Pronunciations bu-lu-un and gu-ud/gu2-ud/gu-du of the sign BALAĜ. Selz 1997:195n153 suggested an onomatopoetic ‘blang’ as pronunciation of what is conventionally transliterated as balaĝ. Bu-lu-un may indeed have been pronounced ‘blong’ or similar. Michalowski 2010a:221–222 considers the word gu-ud/gu2-ud/gu-du = gud10 and suggests that the term GUD.BALAĜ could be understood as gudgud10, “possibly an archaizing late creation that has no equivalent in earlier phases of the Sumerian language, and has as such nothing to do with the balag.” I believe the word “bull” was written with the balang sign when it designates a balang-god.And so the transition of Hathor (Cow-Goddess) and Sumerian Cow-Goddess into patriarchal Bull God:

Lady Bolt of the Sky (Ninsigarana) and Lady Well Regarded (Ninigizibara in women’s Sumerian and standard Sumerian), the two balang-gods of Inana. [118]

42 Her beloved shining [129] balang, Lady of Plenty, [ ],So the Moon-God Sin has the most Lyre harp-god attendants - shamanic singers:

43 … ly intones the holy song, a praise full of love,

44 plays for her the shining up(-drum), the shining balang.

45 Sum. text: The … lamenter rises before her, Nin-Isina,

Akk. text: The lamenters with that prayer to Ninkarak

46 so that An, Enlil, Enki, (and) Ninmah be appeased. [130]

47 After the exalted lady is made to feel good in her dwelling in Egalmah,

48 the king slaughtered a bull for her, and many rams in addition. [131]

A master-god could have several balang servant-gods. The moon-god had eight; the sky-god An and war-god Ningirsu seven; the mother goddess, the weather-god, and the sun-god six; none had five, two four, and one three.

‘Balang of the Day of Laying’ (balaĝ u4 nu2-a), that is, the day of invisibility of the moon. The moon’s absence was apparently feared despite its regular and predictable occurrence. [121] In Umma, this balang belonged to the household of the goddess Nin-Ibgala, an Inana-figure hailing from Lagash and venerated in Umma. A Girsu record of skins left over from small cattle offerings lists five skins from offerings to the divine balang (dbalaĝ), or ‘balang-god’ (diĝir-balaĝ) for as many months of the year Šulgi 39, and twelve skins for the full year of Šulgi 40 (TCL 5 5672). This would have been the balang of the day of laying.

Yet the harp Calf of Sin is likely in direct reference to the moon-god.That's right - you read it here - Original Sin is the Moon energy from alchemical meditation as 666. haha.

Professor John Curtis Franklin Thanks Heimpel:A woman of valor: Jerusalem Ancient Near Eastern Studies in Honor of ...

https://books.google.com/books?isbn=8400091825To see this we will consider two Sumerian hymns to the Moon-god, Nanna-Suen, that were studied by my teacher Professor Wolfgang Heimpel in the Festschrift for Ake Sjoberg, where the stars are referred to as cows and cattle, living in heavenly cattle pens.“

It was at this same time that Anne Kilmer put me in touch with Wolfgang Heimpel, who had undertaken a first survey of Mesopotamian balang-gods in 1998; my request to reprint his list led eventually to the magnificent study with which this book concludes. I am honored that he threw his lot in with mine.As Dr. John Beaulieu notes - the Lyre of Hermes if 4 strings and the Fire of the Tetrad (the one as the octave note) is alchemically put into the EArth (the 4 as the double octave) to create alchemical Qi or Prana from the Steam - the Aion or Air as the kundalini energy from the water being cooked via the Golden Tripod: John Curtis Franklin:

In the Homeric Hymn to Hermes the lyre has the “god-filled voice” (θεσπεσίης ἐνοπῆς, 421) traditionally ascribed to singers (cf. θέσπιν ἀοιδήν, 442), and is itself called a “singer” (ἀοιδόν, 25, cf. 38) and “muse” (τίς μοῦσα; 447) who “teaches” (διδάσκει, 484).Interesting!! So Hermes caused Apollo to switch from Dionysian music to the 4-string Lyre!

But when the divine shepherd was about to drive his cattle back into Pieria, Hermes, as though by chance, touched the chords of his lyre.

Hitherto Apollo had heard nothing but the music of his own three-stringed lyre and the syrinx, or Pan's pipe, and, as he listened entranced to the delightful strains of this new instrument, his longing to possess it became so great, that he gladly offered the oxen in exchange, promising at the same time, to give Hermes full dominion over flocks and herds, as well as over horses, and all the wild animals of the woods and forests. The offer was accepted, and, a reconciliation being thus effected between the brothers, Hermes became henceforth god of herdsmen, whilst Apollo devoted himself enthusiastically to the art of music.

Ah ha!!

4 string Lyre of Hermes.

But Philolaus messed this up!!

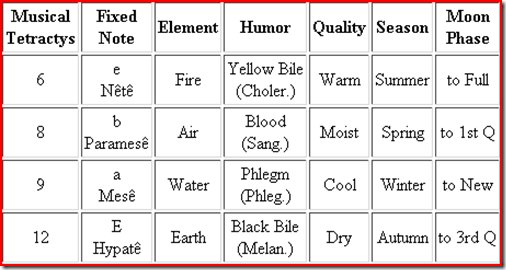

It is generally believed that the Homeric Phorminx (Lyre) had three or four strings. Some believe that they were tuned to the Musical Tetractys E-a-b-e as given here; others believe they were tuned to A-B-C-E or to the Elemental Tetrachord A-B-C-D (Anderson 47, 63, 199; Godwin HS 194, 451n16). This chart accepts the Tetractys tuning (6:8:9:12), because of its esoteric importance.

http://opsopaus.com/OM/BA/ source of the above Pythagorean Hermes alchemy chart

The Aulos (a reed instrument) often has four finger holes (Barker I.15; Anderson 141). Normally the Greeks played Double Auloi, each having four holes, perhaps corresponding to the two disjoint Tetrachords of the octave. Likewise some early Lyres have eight strings in two groups of four. See The Planetary Heptachord on the two Tetrachords in the Octave. The Musical Tetractys defines the ratios of the fundamental intervals of Pythagorean Harmony: 6:12 = the Octave (1:2), 6:9 = 8:12 = the Fifth (2:3), 6:8 = 9:12 = the Fourth (3:4), and 8:9 = the whole tone. The structure is two interlocking Fifths (6:9, 8:12), which are equivalent to two Fourths (6:8, 9:12) and the Tone of Disjunction (8:9) between them (as in the Greater perfect system and the Planetary Heptachord). (Increasing numbers correspond to lower pitches because the numbers represent lengths.)

One side shows a lyre-player seated, surrounded by quadrupeds like an Orpheus, and playing an instrument of at least six strings; that he is enthroned is suggested by the chair’s monumental proportions. The other side shows him (or a twin?) returning from the hunt, leading a captive bull; he carries a quiver of arrows on his back. By what name would the painter have known this figure? Bow and lyre make the Classicist think first of Apollo. Yet the Greeks had no monopoly over this ancient idea. We have seen a probable example from Ugarit in the Tale of Aqhat. [58] There is also Kinyras’ syncretism with Kothar, Aqhat’s bow-maker. [59] The bow is besides an attribute of the WS god Resheph, who was equated with Apollo by Phoenician-Cypriots. [60] But a fourth-century bilingual inscription from Tamassos qualifies both Apollo and Resheph as ‘Alashiyan’, so that we must also assume a pre-Greek, pre-Phoenician figure whose powers overlapped with theirs. [61] The vase vividly illustrates the problem of isolating indigenous gods in the Cypriot iconographic record. It would be no less reckless to suppose that the painter intended Apollo and Apollo alone, than to insist upon seeing only Kinyras here.

Professor John Curtis Franklin in earlier work notes the connection of the Archer Bow with the Harmonics of Yoga philosophy in India (Vedic) and Iranian (Zoroastrian) culture.

the Pythagorean

Perfect Fifths music scale was documented in the 2nd millennium BCE based on

the Sumerian musical terms of some of the cuneiform texts. Professor John

Curtis Franklin, email communication, April 12, 2011.

The yogic goal of bodily and spiritual balance is consonant with the Indo-European notion of ‘measure’ which surfaces as a cardinal attribute of the cognate ‘medical’..., and which is the essence of ‘meditation.’ In Greece we find ideas of harmony applied extensively to the body, often (but not exclusively) in Pythagoreanizing sources as a concomitant to the belief that the mind or soul is simply the ‘attunement’ of the body – the Harmony which supervenes on itsharmonized components….

John Curtis Franklin, “Harmony in Greek and

Indo-Iranian Cosmology,” The Journal of Indo-European

Studies, Volume 30, No. 1 and 2., 2002, p. 13.

Studies, Volume 30, No. 1 and 2., 2002, p. 13.

....................in both cases the lyre is held by a mourner, not actually played. [85] The significance of this is quite clear in the famous scene of the Nereids or Muses mourning Achilles: the lyre is the hero’s own instrument, now silenced (Figure 36). [86] In the second case the lyre is held, appropriately, by a paidagōgós. [87] These images are to be connected rather with the tragic trope that occasions of death and war are ‘lyreless’ (ályros)—lacking the festive ease-of-mind normally associated with lyre-music and choruses. [88]

The text is a treaty between Mati’el of Arpad and a nearby rival, Bar-Ga’yah, and contains numerous curses for whoever breaks its conditions. In one of these, the silencing of lyre-music epitomizes the desolation inflicted on Arpad if unfaithful:

There is a similar musical stipulation in the N-A vassal treaty between the same Mati’el and Assurnerari V (754–745), this time combined with a typical agricultural curse: “may his farmers not sing the harvest song in the fields.” [119]Nor may the sound of the kinnār be heard in Arpad; but among its people [sc. let there rather be] the din of affliction and the noi[se of cry]ing and lamentation. [118]

Whatever the exact intention, the stand is important for attesting on Cyprus, already in the pre-Greek period, an ideologically-charged conjunction of music, metal, and kingship—all three important mythological attributes of Kinyras.

No comments:

Post a Comment